Astronomers taking a close look at our nearest neighbor galaxy have made a highly unusual and model-challenging discovery; the vast majority of its satellite galaxies appear to be pointing in our direction.

According to our best model of galaxy formation, the standard model, galaxies grow as smaller dwarf galaxies are pulled in by gravitational interactions, aided by a vast amount of dark matter. Smaller satellite galaxies we see around larger galaxies like Andromeda or our own Milky Way are thought, essentially, to be there because they haven't fallen in quite yet.

"Astronomers suspect that dwarf spheroidal galaxies may be leftovers of the kind of cosmic objects that were shredded and melded by gravitational interactions to build the halos of large galaxies," NASA explained in August 2024.

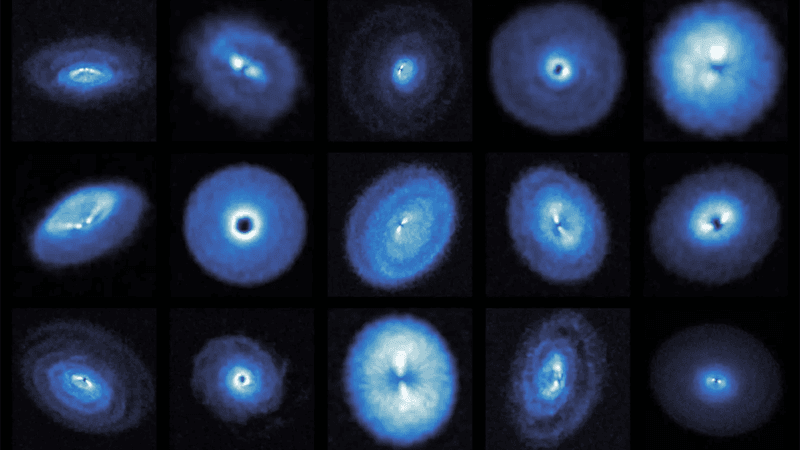

"Curiously, studies have found that several of the Andromeda Galaxy’s dwarf galaxies, including Andromeda III, orbit in a flat plane around the galaxy, like the planets in our solar system orbit around the Sun. The alignment is puzzling because models of galaxy formation don’t show dwarf galaxies falling into such orderly formations, but rather moving around the galaxy randomly in all directions. As they slowly lose energy, the dwarf galaxies merge into the larger galaxy."

That problem, identified by earlier studies, has been amplified by the new study. That study looked at Andromeda, also termed Messier 31 or M31, and found that its satellites are not in the random distribution that cosmologists expect from the standard model.

"All but one of Andromeda’s 37 satellite galaxies are contained within 107° of our Galaxy. In standard cosmological simulations, less than 0.3% (0.5% when accounting for possible observational incompleteness) of Andromeda-like systems show a comparably significant asymmetry," the team explains in their paper. "Around 80% of M31’s satellites lie within a hemispheric region facing the Milky Way."

A visual representation of what that looks like, from the always excellent Anton Petrov.

According to the team, the asymmetry could pose a challenge to the standard model of cosmology.

"Even when accounting for the look-elsewhere effect, similarly lopsided configurations of satellites only occur around <0.3% of M31 analogies in ΛCDM cosmological simulations, and no single simulated system can simultaneously reproduce the population-wide nature of the observed lopsidedness," the team writes.

"At present, no known formation mechanism can explain the collective asymmetry of the Andromeda system. In conjunction with M31’s plane of satellites, which holds a similar degree of tension with simulations, our results present the satellite galaxy system of Andromeda as a striking outlier from expectations in ΛCDM cosmology."

However, before anyone declares our best model to be severely lacking, astronomers need to rule out other possibilities, such as that distance measurements of fainter satellite galaxies are inaccurate, or Andromeda and its satellites being a strange outlier with an unusual recent history.

"The following is speculation, but I expect the underlying culprit behind the M31 system’s discrepancy with cosmological expectations to be some unique accretion history," Kosuke Jamie Kanehisa of the Institut für Physik und Astronomie at Universität Potsdam in Germany, and lead author of the paper, told Space.com. "The fact that we see M31's satellites in this unstable configuration today — which is strange, to say the least — may point towards many having fallen in recently, possibly related to the major merger thought to have been experienced by Andromeda around two to three billion years ago."

Further observations of Andromeda's satellites, particularly the fainter ones, are needed.

The study is published in Nature Astronomy.